Components

The components, the distilled spirits that go into the blend, are of course central to a whisky’s flavour profile and character.

A standard Blended Scotch Whisky contains a blend of one or more single malt whiskies and one or more single grain whiskies. Here, it is generally stated that the stronger malt spirit provides the predominant flavours, while the grain spirits provide a balance and texture.

However, while true, this assertion is an overly simplistic overview of the intricate relationships at play.

While providing unique flavours themselves, it’s through the component spirits’ interaction with one another, and the cask, that new expressions, flavours, and textures are unlocked. The eventual output being far superior to the sum of its parts.

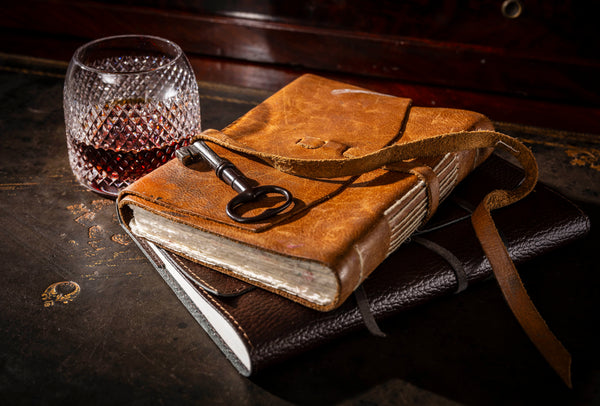

Thus, it is better to think of spirit components as building blocks or ingredients that act as keys to reveal and release the blended whisky’s real essence.

The measures and balance of these components is where generational expertise and craft come to the fore. The blender will decide which component spirits to use and in what quantities to achieve the desired result.

If we take the example of blended grain whisky, the individual qualities of component spirits are clear to see.

Far from simply diluting single malt spirits, grain whisky alone offers a whole spectrum of tastes, textures, and aromas. Used in varying quantities (and with different maturation cycles and casks), diverse flavours can be uncovered and expressed through different grains – resulting in finished whiskies that are entirely unique.

The Eight Grain, our 40-year-old blended Grain Scotch, for example, unites grains from eight of Scotland’s grain distilleries, both active and closed. The whisky is rich with aromas of baked sugar and caramelised banana – finishing with a characteristic creaminess and deep decadent notes of stone fruits.

While, at the other end of this range, our 37-year-old A Breath of Fresh Air, another blended grain whisky, takes on a completely different character, owing largely to the makeup of its components.

Aromas of spearmint, pineapple, crushed mint, and dock leaf are instantly welcoming on the nose, invoking imagery of Scotland’s verdant countryside and herbaceous meadows in Spring. This lighter, almost minty quality carries through on the palate – with bright citrus notes and a crisp mouth-watering dryness.

The diversity of these blended grain whiskies goes to show that even without the stronger flavours of malt spirits – whiskies can take on dramatically different qualities and character depending on the balance of component spirits used.

Timing

The point at which these component spirits are blended, and the length of their maturation has a considerable impact upon their eventual taste, character, and texture.

A bottle like The Long Marriage, which was blended three years after its initial distillation in the 1960s and matured for over 50 years, provides a flavour that can only be achieved through the slow passing of time.

Its character is undoubtedly rooted in history, with aromas evocative of Victorian decadence, stately homes, and candle wax and a rich palate of cinnamon and spices.

The interwoven layers of taste are perfectly balanced, mature, and indulgent – the result of a half-century long interaction between its component spirits and a single sherry cask.

Here, the blender will have sampled the spirit throughout its maturation until the character and taste of the whisky reached perfection – or, in other words, until the spirit took on enough of the flavour or profile of the cask.

In rare cases, the component spirits are sometimes blended straight after distillation – providing a remarkably unified taste profile.

Having matured together for decades, the component spirits become largely indistinguishable – taking on a character and flavour of their own.

This is the case for Blended at Birth whose grain and malt components were married as a new make spirit in 1965. The whisky has taken on a multi-faceted, complex profile after being matured for over 50 years in ex-bourbon American oak with rich notes of marzipan, Dundee cake and leather on the nose followed by pleasing tannin-rich herbal tea on the palate and a cool, minty aftertaste.

By comparing these whiskies, we are presented with a clear reflection of how the time between a spirit’s distillation and its blend affects its final output – whether the components were strong in flavour originally as individual spirits or built in intensity as one.

Maturation

Casks, the oak barrels in which the spirit is matured, perhaps play the most important role of all.

Put simply, maturation in casks is what makes a spirit a whisky – and for Scotch at least, this aging period must have a duration of at least three years.

Once more, it’s through a distiller’s expertise that casks are selected, with each barrel providing its own unique qualities.

Across Scotch whisky production, some of the most common cask types are as follows:

- American Oak: provides woody aromas, with hints of spice, soft vanilla, and tobacco.

- European Oak: generally used initially for sherry production, European Oak provides a distinctive ruby colour and mouth-drying quality with flavours of spices, dried fruit, and resin.

- French Oak: a less common cask that is synonymous with more distinctive spiciness.

A distiller also considers the age, past usage, and qualities of the cask – whether it is a fresher cask (providing more prominent notes) or a cask that has been used several times before (which may have more of a neutral impact).

The cask provides the arena within which the component spirits interact and engage with one another. And, in doing so, allows for endless expression and innovation.

The Tops, our Speyside blended malt Scotch, is a strong demonstration of this diversity and the varied flavours achieved through long-term maturation.

Laid in Spanish ex-sherry casks for 33 years, the influence of the cask’s past usage is evident just by sight – with the bottle’s rich walnut colour offering hints of ruby as it catches the light.

On the palate, the whisky’s initial sweetness makes way to a warm, drying oak character with touches of sherbet.

Taking this a step further, it’s also possible to begin this cycle once more through a second maturation period – emphasising a certain taste or encouraging an already-matured spirit to express new characteristics.

Aged first in a combination of European and American Oak and then taking on a second fifteen-year maturation in ex-bourbon barrels, The Next Chapter is an excellent example of the new life a whisky can take on through this process.

Its secondary finishing period has added fresh vigour to the whisky, contributing a deeper layer of complexity with dense notes of toffee on the nose and a rich, creamy mouthfeel.

Yet another example of how maturation processes can be altered and experimented with to uncover new characteristics.

Whisky’s enduring appeal and allure is rooted in the complexity of interactions that occur between the initial harvesting of grain to the bottling of the finished spirit.

When it comes to blends, another layer of complexity is added – providing an opportunity for further experimentation and expression.

In this piece we’ll look at just some of the numerous considerations and processes that are considered when blending a fine, luxury whisky.

Without providing in-depth technical information, the article acts an overview to help us better appreciate and understand the core relationships at play and their result on the blend.

For simplicity, the core criteria are divided into three key areas – the component spirits involved, the timing of the blend, and the spirit’s maturation. However, it’s important to note that it’s the interrelationship between each of these elements that contributes to a whisky’s overall character and taste profile. They are inextricably linked to one another and the effects of one cannot ever truly be separated from those of the other.

It’s Ready When It’s Ready

What’s clear across each of these areas is the importance of human expertise and decision-making. At each junction, a blender must decide where to take the whisky on its journey – from cask selection, to age time, to component balance, and beyond.

For many large-scale, mass-produced blends these parameters are fixed. The component quantities, distillation parameters, and maturation cycles remain the same, ensuring an identical output with every blend.

However, House of Hazelwood is rare in this respect.

Our selection celebrates the diversity of different bottles, showcasing the experimental and the elusive.

Relying on generational expertise, we have no predetermined timelines for the whiskies in our collection, monitoring the casks until our master blenders dictate that the whisky has reached its state of perfection.

In short, it’s ready when it’s ready.