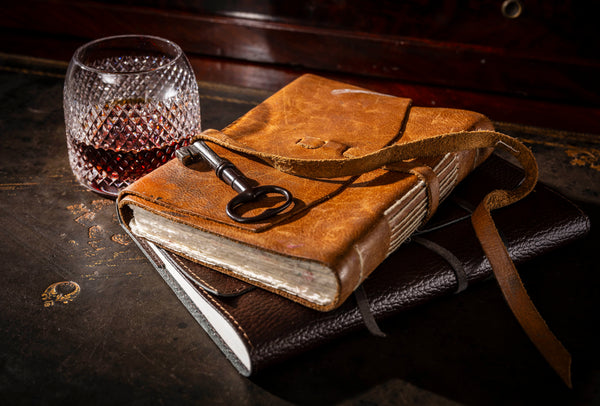

For all the science, sometimes whisky – and particularly rare old Scotch Whisky – takes on characteristics that are not easily explained.

When it comes to the maturation of a rare old Scotch Whisky, if records about a whisky’s provenance are limited at best (a not-so-uncommon occurrence when dealing with whisky over fifty years old) then we must rely on our greatest olfactory resources – our nose and mouth – to help deduce a whisky’s secrets.

From time to time, casks buried deep within dunnage warehouses may be forgotten for decades, only to be unearthed by accident, or perhaps uncovered by an unsuspecting warehouseman – a gift left as an experiment by a whisky maker of the past. When sampled, the results can both thrill and baffle blenders – and the allure of the whisky’s inherent mystery strikes once more.

There are multiple factors that can influence the final presentation of a whisky, but none quite so important as perhaps time and the wood policy behind a whisky maker’s cask selection. Even so, aspects such as terroir, provenance and even the conditions on the day of distillation may have an influencing factor on the final spirit.

What are the influencing factors in a whisky’s flavour?

The whisky making process can mystify even the most avid of enthusiasts. Almost every element of the process has a team of dedicated professionals working behind the scenes, experts of microscopic detail in their own speciality.

With such dedication comes the understanding of the wider whisky making – and every whisky maker, no matter what stage of the process they guard over, appreciates the wider ecosystem – and the roles each stage plays in the final flavour.

Raw Materials – Grain and Barley

There are conflicting schools of thought on the role of grain or barley and if the varieties used have a tangible impact on the final flavour. Certainly, the medium of cereal used does define the profile of the whisky itself – for instance, barley offering a toasted quality versus the sweeter profile of a grain.

Some distillers strongly assert that the type of barley or grain used can be distinctly detected by flavour, however, this is an age-old debate that has yet to reach a consensus. Varieties of barley and grain are often rotated to mitigate overreliance on any particular type in the event of crop disease. The use of cereal ultimately attempts to achieve one thing, especially in the way of mainstream whisky production: consistency.

Source Water

The source water is often the pride of a distillery’s whisky making process. Whilst it is true that the source water is an integral part of distillation, the impact of water on a whisky’s final flavour is tempered and minimally influential at best, taking the temperature of the water aside.

This said, many distillers seek a softer water source, rich in minerals due to the interactions such components can have on the yeast, indirectly impacting the New Make spirit profile.

Malting

Malting, the process of partially germinating grain, is widely accepted to influence the flavour of a whisky, specifically where the use of peat is concerned. The first part of the process, known as “steeping”, sees the raw grain material soaked for an extended period of days until it germinates. At this point intense heat is applied – known as “kilning” to halt the process when it is deemed that enough starch in the process has been converted into sugars for fermentation.

During the kilning process, some whisky makers may opt to burn peat to dry the grain – and it is at this point that the most obvious impact in flavour can be seen, adding phenols to the grain which will later translate into a smoky yet sweet New Make spirit.

Fermentation and Yeast

After the raw material of grain has been processed and sent to the distillery as a flour, it is added to hot water to form a liquid known as “wort”. This wort will have yeast added to it to begin fermentation. It is here that the variety of yeast can influence the flavour, with different strains yielding distinctive profiles – from fruity to herbaceous to buttery and everything in between.

The length of time in which fermentation takes place will also impact the final flavour. It’s for this reason that many distillers consistently conduct experiments on the strains of yeast used and the length of time elapsed over fermentation.

Distillation

Copper stills used to distil whisky rarely conform to any uniform size or style. Whether a pot still is bulbous or slim or a Coffey still has a more-than-average number of condensing plates, the most minuet of details can impact the flavour of the new make.

For instance, a long, sloping, and elongated Lyne arm may owe itself to more reflux being produced in the distilling process, giving way to a fruitier or more tropical character. Similarly, some distilleries may employ the use of cooling jackets during the distillation process to influence a lighter character in the New Make spirit.

Maturation

Largely considered the biggest factor in the final flavours imparted on a whisky, the maturation process offers many facets which can impact the end result.

Time, of course, is accepted as one of the most influential factors, with long slumbers often taking flavours from ripe and light into deeper berry-like qualities, and in some instances, rancio flavours such as forest floors or leather.

The type of cask used is also an obvious contributor – be it ex-bourbon American Oak, European Sherry Butts, or even less commonly used cask types such as Virgin Oak, yielding fiery flavours. The size of cask will play its own role, with smaller cask types such as a puncheon or port pipe concentrating flavours in intensity. The tannins from each cask will seep and settle, influencing the nectar within.

The previous use of casks can also impact flavour – for instance, first-fill casks are likely to impart bolder flavour, than those which have been used before. There is an adage held by some whisky connoisseurs that refill casks are inferior in quality to first fill, however, in the instance of a delicate, light spirit or whisky undergoing maturation for a long period of time, this simply does not apply. Blenders will often select casks based on their subtleties and ability to gently influence – using a light touch to enhance the elegance within.

The final resting place of a whisky, when left in place to slumber for years or decades, may also impact the development of the liquid, although much like the use of types of grain this is often debated. There is reasonable evidence to suggest that airflow and the style of storage, e.g., racked storage in a dunnage warehouse, could play a part.

A Brief Chemistry Lesson on Esters in Whisky

Esters are compounds that formed predominantly during the fermentation stage of the whisky making process when the yeast converts sugars into alcohol.

They are composed of two parts: acid and alcohol. Over 100 different esters have been discovered to date and can each be identified by their notable aromatic profile. The most common such as Methyl Propanoate yield fruity and tropical qualities, but there are those that can produce more unexpected of notes – for instance, Octyl Butyrate wouldn’t be a miss at a Roast Dinner, with its tones of parsnip. Or perhaps for the keen nose that can identify nail polish-esque notes within a glass, the PVA glue-themed Ethyl Ethanoate may be present.

Esters undoubtedly have a significant impact on flavour – and where unusual or atypical aromas and notes appear in a whisky, they can be the cipher to decrypting a whisky’s secrets.

A Breath of Fresh Air with An Unexpected Hint of Mint

When envisioning the profile of an aged rare old grain whisky, depths of butter, honey and toffee are the most likely to come to mind. But within A Breath of Fresh Air, a 37-Year-Old Blended Grain Scotch Whisky from Legacy Collection, lies an invigorating invitation of spearmint, pineapple, crushed mint, and dock leaf.

“A truly magical example of the unexpected transformations that can take place inside a cask.” Simon Thomson, City AM

Such an herbaceous profile will owe elements of its character to the conditions in which it was blended and matured, however, the emergence of the mint like qualities could suggest the creation of uncommon esters such as Methyl Salicylate, a root beer or wintergreen oil styled compound, and Propyl Salicylate – the ester of Spearmint during the fermentation process.

This expression, due to its character, truly is one of kind, and completely unexpected for an aged grain. For the most curious of connoisseurs, securing one of these 417 bottles is a promise to the palate like no other.

The Cask Trials is a Chameleon of a Rare Old Scotch Whisky

The Cask Trials, a 1968 Vintage Single Grain Scotch Whisky from the Charles Gordon range is the exemplar expression of cask maturation and the impact it can have.

This bottling was matured for over half a century – 53 years – with Girvan Grain in a single sherry butt. The time in which the whisky has spent maturing, left undisturbed for decades, has resulted in a character that when tasted blind fools the palate into identifying flavours associated with a well-aged Single Malt.

“The time in the cask makes it hard to think that this is a grain whisky. Dark brooding Sienna brown in colour, the nose does not disappoint with a rich note of dried apricots, dates, and raisins. The finish is long with all those initial fruit flavours to the fore.” Scottish Field

Naturally, as with any sherry-cask maturation of length, notes of dried fruit are abundant, however, unlike a typical grain, characters reminiscent of the use of barley, such as toffee and roasted coffee are intensely present, making all 303 bottles of this whisky a chameleon-like wonder to behold.

A Compound Cacophony within The Old Confectioner’s

What happens when both the fermentation and maturation are as impactful as each other? With the right guidance and guardianship by the whisky maker, the resulting golden nectar appears in the form of The Old Confectioner’s, a 44-Year-Old Blended Malt Scotch Whisky from the Charles Gordon range.

A nose of this sweet shop drop reveals secrets of its fermentation with an abundance of candied fruit on the nose. Looking to our esters to help decipher what happened to some of the component of this blended malt, we can assess the inclusion of a potential ester, Isoamyl Acetate, commonly nosed as Pear Drops.

“There is no doubting the aptness of the name on this bottle – a tour of the jelly sweets, sherbets and even the furniture of an old sweet shop.” Alex Mennie, Luxuriate Life

This blended malt also offers a deep complexity only achievable through extended years of maturation in refill sherry butts. The tell-tale palate of treacle, toffee, oak and the rancio notes of leather allude to its age, and when combined with the candied esters, produces an evocative malt, reminiscent of sweet shops long gone.

Just 256 bottles of this beautifully balanced expression remain.

Rare Old Scotch Whisky – Deciphering the Mystery of Flavour

When it comes to aged and rare old Scotch Whisky, a lack of documentation or records creates a mystery which entices the epicurean in us to uncover.

By consulting the various stages of the whisky making process, there’s not much that cannot be deduced using the science – however, from time to time, it can seem as though an enchantment has been put upon a cask, and no matter how hard we try to coax them, some whiskies will simply refuse to give up their secrets.