Every part of the whisky production process influences the final flavour in some way. An often-overlooked part of the process is the phenomenon of reflux within copper whisky stills, and its ability to transform new make spirit into a tropical triumph.

From the esters produced during fermentation, to the flavours imparted over a long, sherried slumber in cask, every part of the whisky making process plays its own role in how the final packaged whisky presents itself.

Perhaps the most iconic symbol of the industry (beyond the cask) is the copper still, synonymous with the romance of whisky making. These very stills that are responsible for producing new make spirit can be in themselves an influence on flavour, and the processes which occur within the still, can contribute to the body, mouthfeel and even flavour of a new make spirit.

Copper whisky stills: a brief note on distillation

To understand the role of reflux, an understanding on the process of distillation is required. When conjuring an image of a copper whisky still, the traditional bulbous pot still is usually the first to come to mind. These are the stills that are most often used in the batch production of single malt whisky. Pot stills in whisky distillation are made almost exclusively from copper.

The other, lesser thought of still is the towering giant, the column still (also known as a Patent or Coffey still) which operates in a model of continuous distillation to facilitate the production of grain whisky. Unlike the pot still, column stills may be made of stainless steel, copper, or a mix of the two, although internal components are likely to be made of copper.

The process of distillation via a pot still or column still is broadly similar, with some key changes in production depending on the still type.

In the production of malt whisky, the wash is distilled first in a pot still, named as the “wash still” to separate the alcohol from the mix, before moving into the “spirit still” for further distillation.

For grain whisky, the wash will be distilled in the column still – added into the top, passing through two columns – the rectifier and analyser – undertaking the same relationship as wash and spirit still in malt whisky production.

A phenomenon within the stills can occur known as reflux – this is when vapour within a still meets a cooler part of the still and in turn condenses and falls to the bottom, to be redistilled.

Why are whisky stills made from copper?

Historically, stills were made of any hardy material that could be shaped – including less obvious mediums such as ceramic. The use of copper has been widely adopted by spirits distillers in both Scotch and around the world due to its capability to conduct heat efficiently to the temperatures required to distil. By its nature, it is easily malleable, enabling coppersmiths to design stills to the distillery specification.

Copper stills are reasonably resistant to wear and tear, especially in the face of producing up to 10 million litres in its lifetime. With good maintenance, they are considered to have a lifespan of up to 20 years. In modern distilling, the commission and replacement of such stills is a considerable cost and as such, distillers out with Scotland have dabbled with the use of more affordable and readily materials such as stainless steel in whisky making. Although there have been some successes in using different mediums, there have been considerable challenges, such as inefficiencies with heating or an inferior quality of new make, meaning that the use of such materials is rare within whisky production.

What is the impact of reflux?

The process of reflux is especially important for some distillers, especially when commissioning the smithing of new stills. Some distillers will actively seek to capture a greater excess of reflux as this process of condensing and redistilling lends itself to the creation of a lighter-bodied new make spirit, which is often fruitier and tropical in nature.

As such, distillers will actively instruct coppersmiths to create bulbous or exaggerated shapes in their stills to enhance this effect. Similarly, distillers may also opt for the use of a cooling jacket to further aid condensing and exaggerate this character.

Reflux: paying homage to tropical tastes

Of course, there are a myriad of reasons as to why a whisky may take on tropical characteristics outside of the process of reflux – for instance, the esters formed at the stage of fermentation, or the cask in which a whisky matures can all contribute to a tropical bonanza. But, even so, looking to techniques such as reflux can allude to and help us to demystify the conditions in which a rare and well-aged Scotch has come to be. In the spirit of flavour-led endeavours, why not dip your toes into a taste of the tropical and attempt to uncover the stories lie that within the House of Hazelwood inventory?

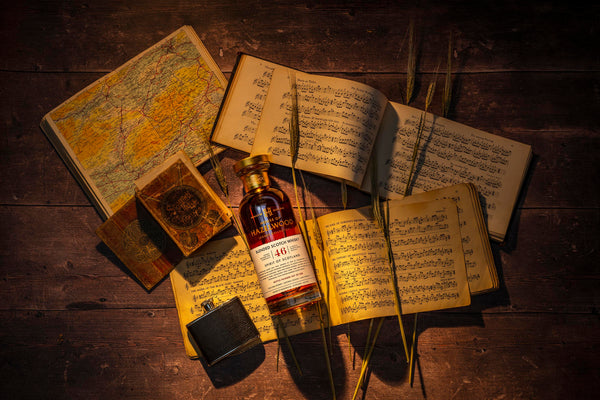

Sunshine on Speyside

If an era could be defined by flavour, the 1980s would be an expression reminiscent of unapologetically gaudy cocktails, composed of pineapple, mango, and sherbet fizz.

Sunshine on Speyside, a 39-Year-Old Blended Malt Scotch Whisky, is just that: a tale of tropicana.

Offering up notes of fresh pineapple and barbecued fruit on the nose, the palate evolves into cacophony of Caribbean flavours with delicious, charred fruit, zesty citrus, and caramelised smoke on the palate. With just 398 bottles of this drop available, this bottled sunshine will soon be gone.

Spirit of Scotland

Perhaps an unexpected character from an expression dubbed the Spirit of Scotland, this expression offers a moreish mouthful of lemon zest, meringue pie and smoke against a backdrop of scrumptious home baking.

Offered as a 46-Year-Old Blended Scotch Whisky, this blend was created first in 1994 to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the very first recorded reference to Scotch Whisky, before a secondary slumber in casks for a further 28 years. The resulting spirit is mouth-wateringly smooth – and a true temptation of the tropics lies within all 528 bottles.

The Lowlander

Those searching for an elegant and lightly bodied Scotch Whisky need seek no further than The Lowlander, a 36-Year-Old Blended Scotch Whisky, epitomising the region of the grassy lowlands of Scotland.

Emoting evocative notes of flinty granite, meadow grass and vintage cars on the nose, the palate progresses into a burst of spun sugar and star fruit, concluding on a lengthy, lasting finish. Just 432 bottles are left of this exceptional expression, the ideal companion to muse upon in the shade of the scorching summer sun.